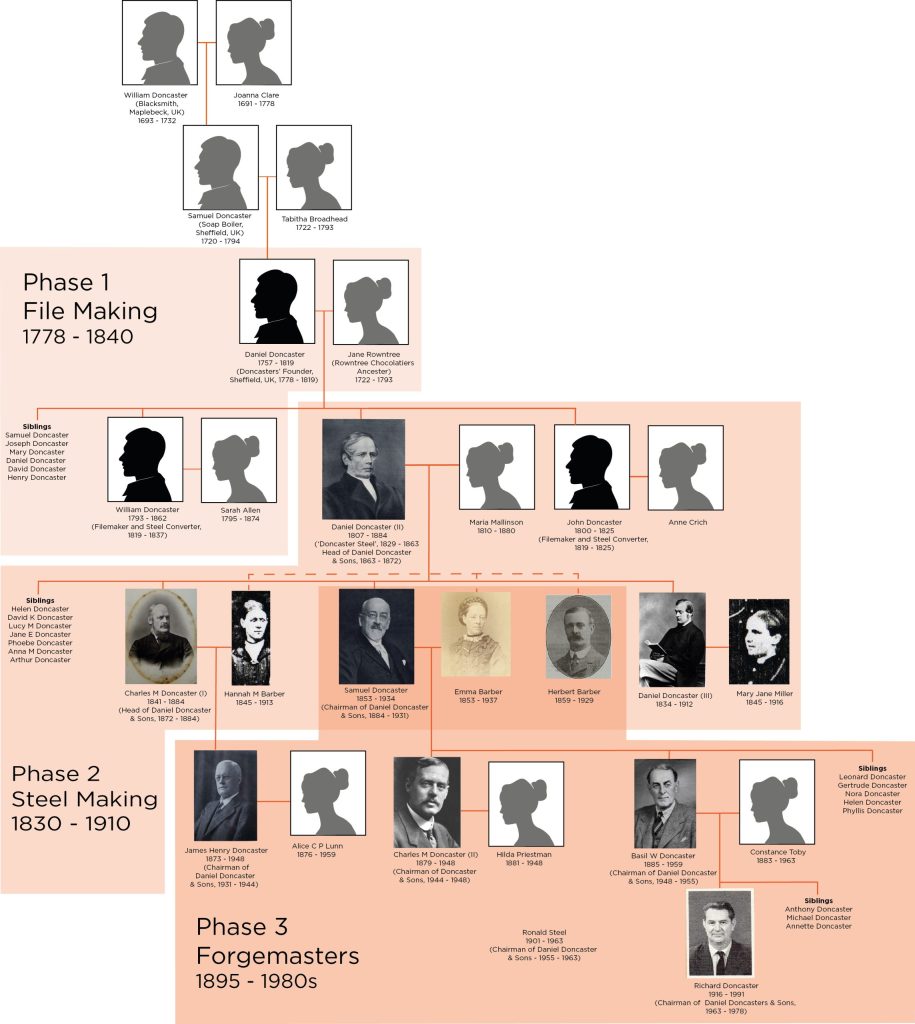

FIVE GENERATIONS OF GROWTH

After Daniel Doncaster started his business in 1778, there were three major phases of growth for the Doncasters family. The final phase continued to be delivered by the last member of the family to be involved in the business; Richard Doncaster, who was Chairman of Daniel Doncaster & Sons up until 1978.

These three phases of growth overlapped and were complementary. Each development coincided, or was consequential with, a social era of change. The Doncasters family made use of existing expertise and knowledge, developing new products or processes based on well established industries.

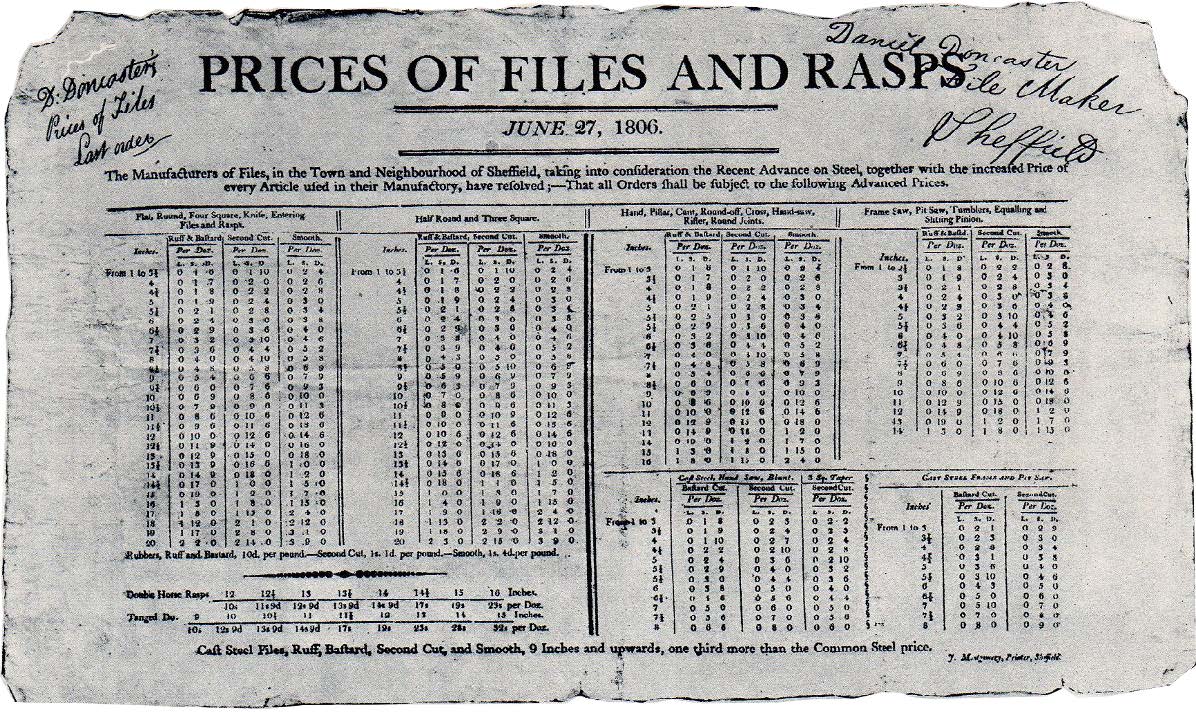

File making was started by Daniel I who was granted his Freedom and Trademark on 29th May 1778. He was self-employed and was followed by his oldest son, William Doncaster, who later extended the business activities.

Steel making stemmed from Daniel II Doncaster, the third son, who started independently as a merchant and importer of Swedish iron, which was converted into steel. Eventually William joined with Daniel II and the file business declined.

Merchanting and steel converting was added to by Charles I Doncaster with steel melting (c1870) and Samuel Doncaster continued this into the 20th century, followed by James Henry Doncaster.

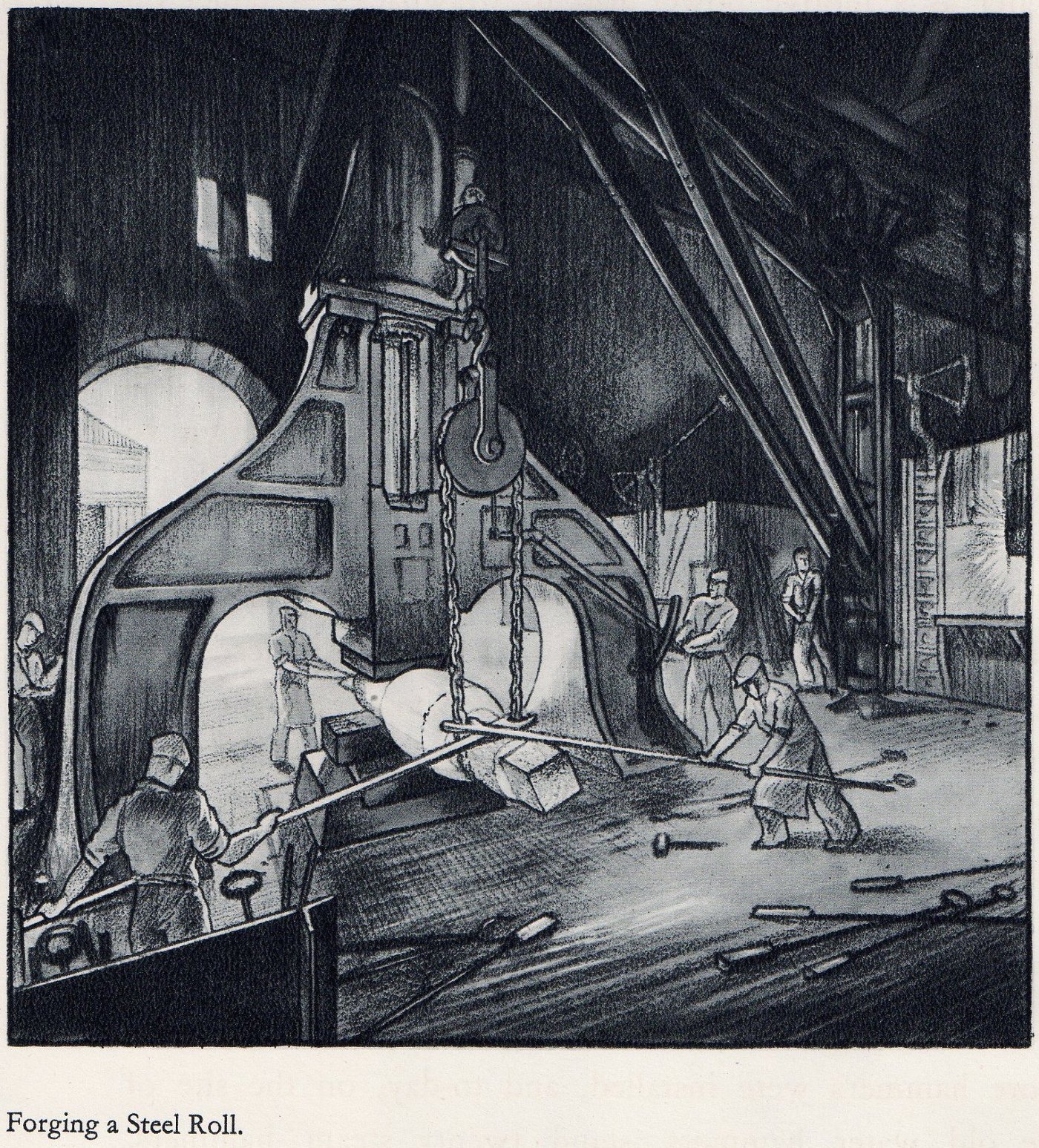

Just as converting was closely related to cutting tools, so steel melting was related to forging; first as a secondary process for ingots and then to produce forgings (1898). This stemmed from Charles II Doncaster, was supported by Basil Doncaster, and was continued by Ronald Steel, the only non-family member to chair the business. Ronald began working for the company when the business joined the United Steel Companies (1920 – 1936).

The last member of the family, Richard Doncaster continued this forging phase when the business had returned to being Daniel Doncasters & Sons.

Doncasters - Six generations

These phases were prompted by social change and growth.

In 1778 – 1830 there was a need for hand tools as agricultural cutting implements such as files, knives, scythes and sickles. Converted bar was ideal for these products and later on as a base for steel melting. The local trade of cutlery, for which Sheffield was famous, grew from these processes.

In the 1860s, engineering was well established and better-quality steel was demanded for machine cutting tools and a variety of tool steel engineering products. The crucible process supplied such material.

By 1895, transport had developed to require shaped articles in reasonable quantities. A forge was no longer just for ingot reduction or tool steel bars. The era of die forging was taking over from the blacksmith. During the 20th century transport in all forms and capital plant for industry led to sophisticated and specialised forging equipment.

MORE ABOUT THE FAMILY

Records show that the Doncasters family were keen to contribute wherever there was need. Causes included:

- the Holmfirth appeal after the Bilberry dam burst in 1853;

- an appeal for relief of distress in the Lancashire cotton districts in 1862;

- the fund for liberated slaves in America in 1865;

- Filey fishermen’s distress following heavy gales in 1869; a Bulgarian appeal in 1876;

- the great Indian Famine appeal in 1877; and,

- in 1864 the appeal to ‘Relieve the Distress and Suffering Occasioned by the Bursting of the Bradfield Dam’. The Dale Dyke Dam disaster had an immediate impact on the Doncaster company because the flood swept though one of its tilters’ works at the confluence of the Loxley with the Don. It was this heavily populated area that was devastated.

Health care for the poor was another concern for the family, with the family actively supporting the local Infirmary. Local schools for children and adults were also supported by the Doncaster generations.

Interestingly, Daniel II had a special interest in education arising from his and his wife’s experience. Three of their children were deaf, probably from birth; they were the oldest son Daniel III, the youngest son, Arthur, and the fourth of their five daughters, Phoebe.

Daniel III was born in 1834, Phoebe in 1847 and Arthur in 1856, but it was not until after their father attended, in December 1862, the first meeting held in Sheffield concerning the ‘Deaf and Dumb’, that he led the formation of the Sheffield Association for the Adult Deaf and Dumb.

Daniel III was a good lip-reader and learned to speak distinctly. He was involved in his father’s business throughout his working life. Arthur evidently did not learn to speak, but always carried a chalkboard on a string round his neck to communicate. Phoebe became Arthur’s companion and housekeeper; there sadly there is no record of how she communicated.

Daniel was not overly inhibited by his disability, there are a number of reports of his activities in the local papers, notably when he submitted meteorological information. Arthur was seen as one of the most notable members of the family. He became an expert on entomology, providing material, especially butterflies, to the Natural History Museum around the time that the natural history collection was moved from the British Museum to South Kensington.

Daniel and Arthur’s nephew, the sixth Doncaster to head the business, Charles M Doncaster II, was known to be a ‘considerate employer’. His 1948 obituary notice recounts how Charles was responsible for starting a social club at the company, where he participated with the

workers in leisure activities. He is also, in 1921, ‘built a holiday guest house for the workmen and their families, thus spending his share of

the wartime profits.’ Sadly, the guest house was destroyed by fire on 10th September 1938. During World War II Charles, then aged 59, also insisted in taking his turn on firewatching duty, spending one night every week at the main Sheffield factory.

By 1778, when our story begins, Sheffield was deemed by many as being the most important industrial centre in the world.

At this time, the migration of populations into the towns was at an early stage. The only power was from wind and water, people and animals; transport was by foot, donkey or horse and cart. Daniel Doncaster started in the traditional business of Sheffield in 1778; that of iron and steel manufacture and the processing of these metals.

Sheffield became a centre of the iron trades because it met all of the requirements for making iron at that time. It had the raw materials to hand, and most importantly abundant water power. The millstone grit from the surrounding hills was ideal for sharpening tools and Sheffield was a centre of the cutlery trade as early as the fourteenth century. Subsequently, in order to make the best quality metal, it had to import Swedish iron and for this its access to a navigable waterway, the River Don, only a few miles from the sea port of Hull, was important. It was not uniquely advantaged; other places, such as the area around Dűsseldorf, were also well provided. What made Sheffield special was that it was here in 1742 that Benjamin Huntsman developed the crucible steel process.

Crucible steel was the eighteenth century equivalent of the silicon chip in the 20th century.

The crucible process made it possible for the first time to make a steel that could cut iron and lower-grade varieties of steel.

The most important machining tool then and for many years was the hand file. Almost any shape can be made using just hand files. The steel files that could be made in the second half of the 18th century by Daniel Doncaster were then used for the smoothing of bearing and sliding surfaces and made the harnessing of steam power more efficient than when Newcomen built his steam engine earlier in the eighteenth century.

In the second half of the 18th century steel files were at the forefront of technology. In becoming apprenticed to a file maker, Daniel was entering the high technology trade of his day.

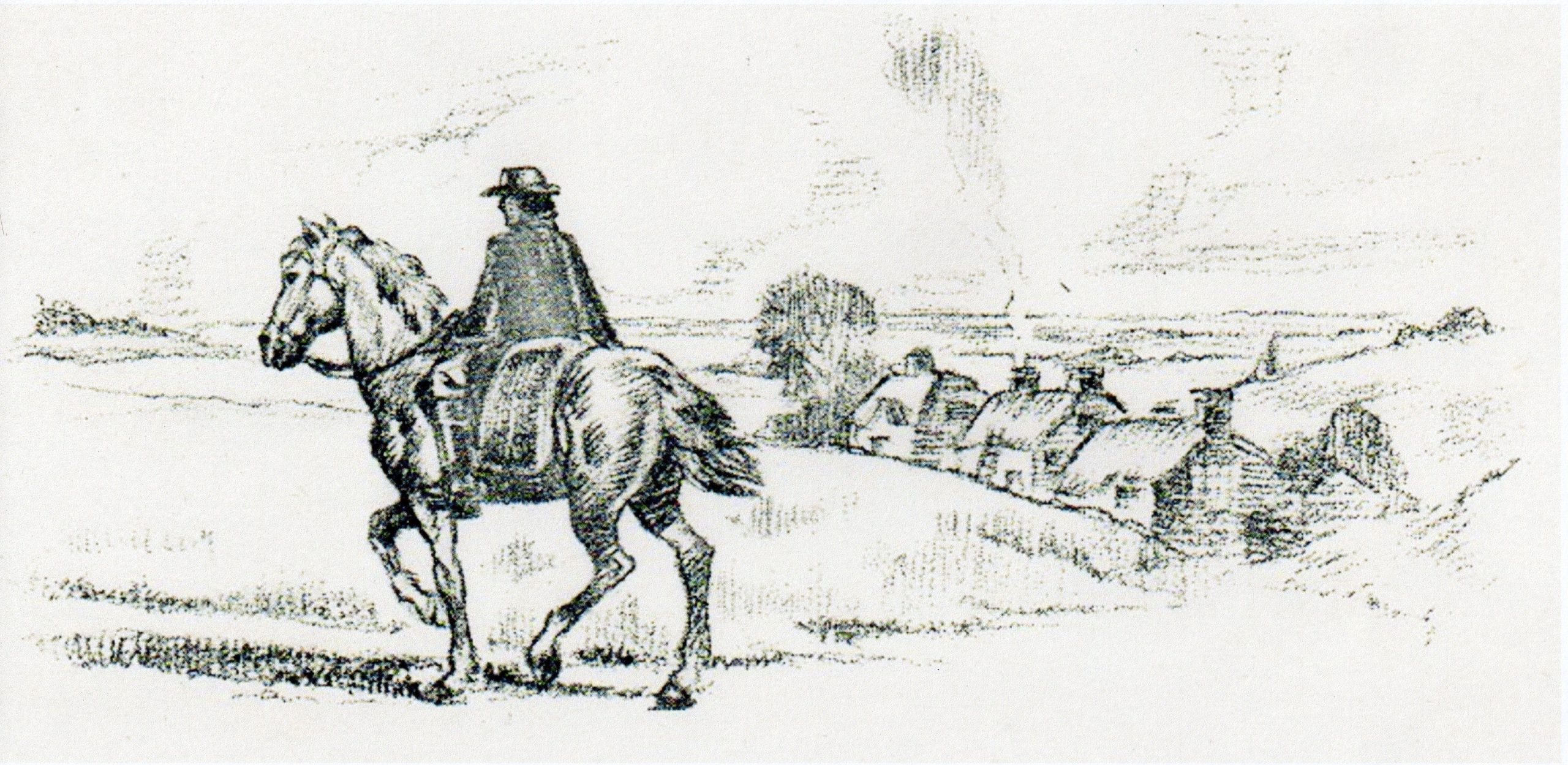

Daniel, his sons, grandsons and great-grandsons stayed in Sheffield. They didn’t move too far from one another as their businesses grew. When Daniel set up his business on his own in 1778 he would have been known in the area as a ‘little mester’. We would now define him as a sole trader. He would spend up to three months each year travelling to collect orders, travelling on horseback.

It was the direct marketing of his product that differentiated Daniel from most of his competitors. His competitors used middle men who obtained the orders and placed the work with a ‘little mester’ who gave him the best price. These middle men took control of the business from early in the nineteenth century, stealing the best designs and having them made by those prepared to offer the lowest prices. Daniel cut these middle men out.

Daniel would travel as far afield as Cumberland, Bristol, London and Birmingham. His best market was in the West Country, where his files would have found their way into the hands of the brass and bronze workers associated with ship-building, for which Bristol was noted. In his old age he took to travelling in a one seat gig, called a sulky, reportedly so that he would not be tempted to give anyone a lift!

Daniel Doncaster’s business was originally run from No. 37 Copper Street, Sheffield. This road was connected to Furnace Hill, where his father was listed as a grocer and tallow chandler, and with Gibraltar Street not far from the Rover Don. There would have been little more than a workshop, equipped with an anvil, manual hammers and coke fires, as well as the home-made hand tools essential to the work. Copper Street was still used in the business until the 1914 – 1918 war but Holden’s Directory of 1811 shows Daniel listed as being at No.12 Allen Street, Sheffield.

Both Copper Street and Allen Street were quite close to sources of steel from tilting works on Green Street and on Kelham Island, though Allen Street had the advantage as it was easier to push a barrow laden with steel along this much flatter street.

In 1817 Daniel acquired Lydgate Hall and its 60 acre farm but continued to live mainly in Allen Street.

When Daniel died on the 2nd of September 1819, his two older sons, William and John carried on the business. In 1821 William and John are listed as filemakers and steel converters at No.12 Allen Street. In 1822, now married, William moved to No.15 Allen Street.

When John died, Daniel II, his other brother was serving an apprenticeship with a draper in York but he joined William in the business in 1829, forming a partnership which is shown in the directory of 1833 as merchants, file manufacturers and steel converters and refiners.

In 1832 the partnership split up. £1,500 of stock was divided equally between the brothers. Daniel took the steel, about a quarter of the total, the rest was in files, which were left for William to sell. The file business continued to be operated by William from the Allen Street premises and Daniel became his steel supplier. This very much echoes the Doncasters of today, with sites in the UK, USA and Germany supplying Superalloys to other Doncasters sites around the world.

William Doncaster became a man of property with a substantial list of dwelling houses, shops and factories in and around Allen Street including the works of Daniel Doncaster and Sons in Copper Street, where there were three converting furnaces, a coke shed and yard in an area of 560 square yards. After William’s death in 1862, the Doncaster Trademark was passed to his widow and brothers, until the mark was then registered later in 1884 for the steel trade which Daniel II took up, laying the foundations for the continuing business.

Daniel II had training in commerce and began the business of buying and selling, and arranging for the conversion of Swedish iron in order to supply the many businesses in the Sheffield area.

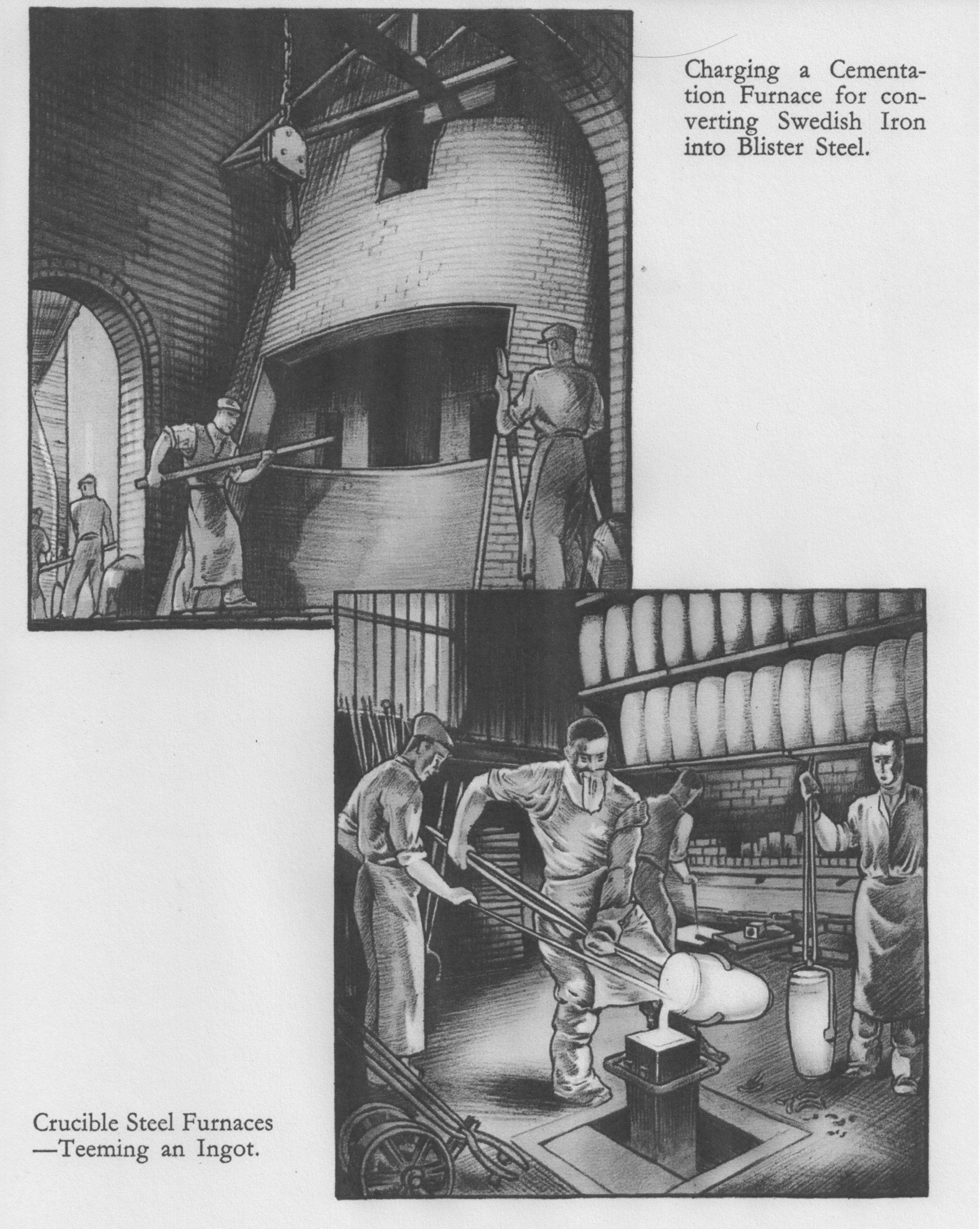

His first step was to become an iron and steel stockholder, buying large batches of Swedish iron from the Hull importers and selling it in smaller quantities to edge tool or steel makers. Some of the trade was for blister steel, made by converting the bar iron in cementation furnaces, others wanted steel from the crucible process and the wider opportunity was for Daniel to arrange for the conversion of the bar iron to meet these requirements; even better to do it himself.

There is confusion in the versions of the Company’s history about the date when cementation furnaces were installed. The Company’s 160th anniversary booklet says that the first cementation furnace installed by Daniel was in 1831, while Richard Doncaster said that the first Daniel installed a cementation furnace in 1817. A note to the accounts for the first year of Daniel’s partnership with his brother suggests that the installation had already occurred by 1830.

The furnaces were in Copper Street. A plan of the Copper Street site from 1834 shows that there were then three furnaces squeezed into a site of 560 square yards.

In 1835-6 Daniel invested almost £2,000 in land and buildings and purchased his father’s orchard from his mother.

The orchard, a few roads down from where Daniel I began the business, was bounded by Ellis Street, Doncaster Street, Matthew Street and Burnt Tree Lane.

The orchard on Doncaster Street became the centre of operations for Daniel and continued as the headquarters right up to 1899. In July 1836 Daniel purchased almost 50,000 ordinary bricks and 2,000 firebricks at a total cost of about £70. Another cementation furnace was built as well as warehouses for the metal imported from Sweden.

Daniel also owned a forge at a site called ‘Kelham Island’ which had a watercourse, or ‘leat’ taken off from the River Don to power wheels which then powered hammers and grinding wheels which were located there and at the back of another site at Green Lane.

Growing demand required more capacity and two more cementation furnaces were built before 1850; there were eventually five such furnaces on Doncaster Street, making a total of eight with those in Copper Street. The last two were installed in 1872.

The maximum extent of Daniel’s conversion business was the output of eight cementation furnaces and eighteen crucible holes, reflecting the nature of a business that supplied a wide range of smaller businesses; a long list of them could be found in his sales ledgers and cash books.

He also supplied Swedish iron and, occasionally, steel to the bigger players, who were soon looking towards the ships plate, armour plate, gun and railways businesses that were opening up, rather than the file and edge tool trades in which they had all started. In its essentials the business remained like this until the end of the century.

Until his sons started to join the business, sometime around 1850, Daniel II was a one-man band. He travelled to Hull to buy his iron, travelled around Sheffield to sell his goods and services, kept the records, using the best accountancy practice, dealt with arranging the stock and scheduling despatches using his local carrier.

When he retired, on December 31st 1872, his third son, Charles, became the head of the Company. Daniel continued to take an interest in the business until his death in 1884. Charles, sadly died a few months after his father, he was only 43.

Samuel, the next son, who had joined the firm in 1874 as Town Traveller after serving a four year apprenticeship with Seeböhm and Dieckstahl, now became the head of the business, taking as his partner his brother-in-law, Herbert Barber, who had joined the firm in 1876.

For the first decade or so under the leadership of Samuel and his brother-in-law, Herbert Barber, the business continued to evolve along the lines established by Daniel II, as importers and converters of iron, steel and related products.

The company had begun to import spiegeleisen (an alloy of iron and manganese); the first record is of it being sold to Dieckstahl in 1865. It was used as a deoxidant and had gained in importance as it helped to mitigate the effect of sulphur in coke fired blast furnace iron. It was in the last quarter of the nineteenth century that alloying additions started to be made to steels; nickel, tungsten, chromium and vanadium additives were used.

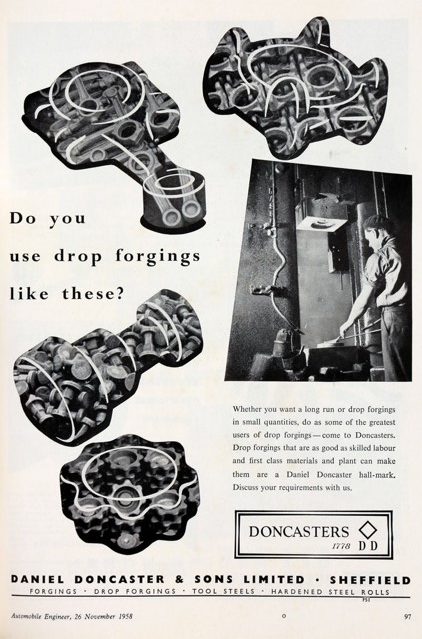

Previously, these could not be introduced in the Bessemer or Open Hearth processes because of alloy losses, so the development of alloy steels gave a new lease of life to the crucible steel business. The first alloy steels produced by the Company were made in 1893. Responding to this new opportunity, in 1898 an efficient 24 hole crucible steel furnace was built to replace the three 6 hole furnaces that had operated up to this time. This furnace was built in the newly acquired Hoyle Street site. They also bought Penistone Road forge to re-equip with steam hammers up to a weight of five tonnes.

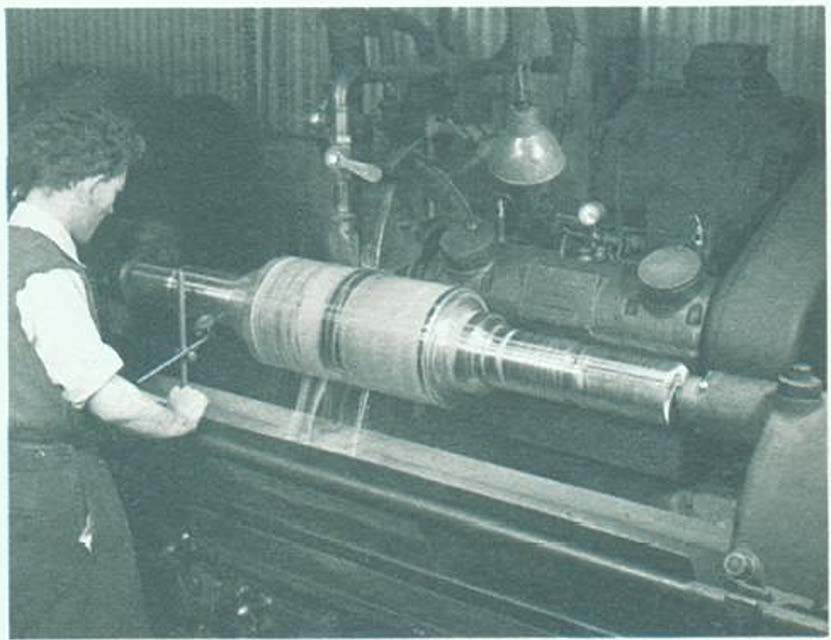

The traditional craft of the melter was to be replaced by the hand and eye of the forge-man, whose experience told him the exact time at which to draw the material from the furnace, how hard and for how long to hammer it, when to re-heat, and when the desired size had been attained. As the years past they grew in skills, embracing the work of more difficult materials, their heat treatment and the use of more complicated equipment.

In the 1900s the history of Doncasters had fully entered its third phase, that of shaping metals to satisfy the many requirements of the new age. They were entering a world of the motor car, the ominbus and the lorry.

When Samuel retired, James Henry, (Harry), son of Charles I Doncaster, became Chairman of the business. Harry, who had been Secretary for many years, was Chairman from 1931 to 1944. He served as President of the Sheffield Crucible Steel Association and took his turn as Chairman as the High Speed Steel Association.

After James Henry retired, Charles M II Doncaster then took on the role of Chairman of the Company in 1944. His tenure was cut short when he died just four years later in 1948. His younger brother, Basil, then took on the mantle and held the position for seven years.

His son Richard became chairman after Ronnie Steel died in 1963. He was to remain as chairman until his retirement in 1978, the bicentenary year. He, like his father, had an interest in Industrial Archaeology and was well known in the Historical Metallurgy Society. Richard was also the second member of the Company to become Master Cutler, the first was Herbert Barber.

In 2023 we are proud to release to the public, for the first time, this archive documentation. These archives have been passed down the generations of Doncaster family members and subsequent owners and employees.